Ch 2.3 | 📃The Constitution

I was never a constitutional scholar, but I was once a practicing attorney. As such, I have studied constitutional law and have at least a basic understanding that I feel is critical to understand how the system is being used against us.

We are getting dangerously close to ending the American experiment. I say “experiment” because that’s what America has been for the past 237 years. The United States of America was founded — not to unify people around ethnicity, religion or culture — but as a bold experiment designed to create a society governed by ordinary citizens, one that gives full expression to the ideals of liberty, justice and opportunity for all. In its time it was a truly audacious idea.

When the founders boldly declared that all men (yes, I know, but let’s stick to the larger point) are created equal and that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed, 5,000 years of rule by hereditary emperors, kings, and feudal lords suggested such an idea might even be contrary to human nature.

Sadly, they couldn’t have predicted the modern world we’re living in and never anticipated that their Constitution would still be governing our lives.

❤️🩹The Founders expected the Constitution to expire in 1796

The Founding Fathers recognized human imperfection and that a tendency to abuse power is ever present in the human heart. They attempted to restrain those in power through a written Constitution that carefully divided, balanced, and separated the powers of government and then intricately knitted them back together again through a system of checks and balances.

It left all powers with the people, except those which, by their consent, the people delegated to the government and then made provision for their withdrawing that power, if it was abused.

In 1787, when the Founders had hammered out the U.S. Constitution in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin told an inquiring woman what the gathering had produced:

"A republic, madam, if you can keep it."

(Side note: The Constitution established a democratic republic, meaning the people elect representatives who ultimately make laws on our behalf, and we all agree to abide by those laws. In a pure democracy, the people would directly make decisions, rather than elect representatives. The framers of our Constitution rejected the Athenian model as “too democratic” for the measured republic they were trying to build. They feared the emotion, corruption and factionalism that had plagued Athens. In fact, they believed that it was this direct form of democracy that led to the downfall of Greece amid a crippling economic downturn.)

Did you know that the United States has the oldest written constitution in the world? Do you know that it was the intention of the framers that it be a living, breathing document?

Writing from Paris just after the French Revolution broke out, Thomas Jefferson argued to James Madison, the primary author of the Constitution, that the Constitution should expire after 19 years and must be renewed if it is not to become “an act of force and not of right.”

Moreover, at the end of the Constitutional Convention, George Washington said:

"I do not expect the Constitution to last for more than 20 years."

Through that lens, you can start to see that the Constitution of the United States is just a set of agreed-upon rules for our democracy and should not be considered an immovable object frozen in time.

In fact, we have adopted 26 amendments to the Constitution, most recently in 1971. While the first 10 amendments (the Bill of Rights) focused on protecting individuals from government overreach, many that followed focused on expanding civil rights and protections. More on this in the section where I discuss inequality in America.

Jefferson addressed this very issue again after he served as president, writing in 1816:

I am certainly not an advocate for frequent & untried changes in laws and constitutions ... but I know also that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind ... we might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.

📃The Constitution derives its power from the majority consent of the governed

We have established the Constitution was never intended to be immutable. Nor was it intended to grant excessive power to elected officials. If those in power are permitted to act in defiance of the Constitution, they only do so because we allow it. In fact, it isn’t actual “defiance” at all because the Constitution derives its power from the majority consent of the governed!

At the end of the day, if our representatives choose to ignore the Constitution or act in defiance of it, then our only recourse is to hold them accountable! As Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence,

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

So, it’s on us to do something to check those in power.

The primary way to hold them accountable is at the ballot box. But today, the ballot box has been "rigged" against us. Gerrymandering allows officials to design districts that virtually guarantee their re-election. Closed primaries shut millions of Americans out of the only meaningful elections. Voting systems make it nearly impossible for anyone besides a Democrat or Republican to win an election. Unless tens of millions of us demand the system change, we will continue to allow the political industrial complex to tear the country apart while those in power remain in power.

This is why we need to "unrig" the system, to ensure we bring common sense and proportionate representation back to our government before it's too late.

🗳️The Electoral College

At the heart of our representative democracy is the Electoral College system. The framers of the Constitution created the Electoral College to theoretically prevent presidential candidates from ignoring the needs of less populous states in favor of highly populated ones.

Moreover, our Constitution was designed to survive an autocratic president who would threaten the rule of law, basic rights and democracy itself. One way to do that was to add a protective layer to presidential elections.

According to Alexander Hamilton, writing in Federalist 68, the founders hoped the Electoral College would help to screen out those who had “[t]alents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity,” and help to guarantee that only candidates who to “an eminent degree [were] endowed with the requisite qualifications'' would be elected president.

That hope has not been realized. In fact, the Electoral College now serves little purpose other than to occasionally prevent the candidate with the most support among the voters (what is often called the “popular vote”) from winning the election. Five men have won the presidency without winning the popular vote, including most recently George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016.

The most straightforward fix would be a constitutional amendment that eliminates the Electoral College. But that is a long process that would face nearly insurmountable obstacles from states that want to protect their outsized influence.

Another option would be a national popular vote plan pushed through state legislatures. It keeps the Electoral College in place, but states that pass the bill would direct their electors to vote for the candidate who wins the popular vote on a national level. It would only go into effect when enough states sign on to guarantee a majority of Electoral College votes (270) would be awarded that way. So far, 17 states and D.C. have passed national popular vote bills, totaling 209 electoral votes.

⚖ Constitutional checks and balances

As you probably remember from your high school civics class (a dying breed, evidenced by the fact that 1 in 4 Americans, according to a 2016 survey led by Annenberg Public Policy Center, are unable to name the three branches of government), the framers implemented a number of structural checks and balances.

Worried about the possibility of a "tyranny of the majority,” they made it more difficult for Congress to easily ignore the needs of minority groups by requiring the support of a supermajority for major decisions.

They added the Bill of Rights to the Constitution to protect various individual rights.

To prevent any one part of the government from becoming too powerful, they created three co-equal branches of government (including a bicameral legislature) designed to work independently and in cooperation to prevent abuse of power.

But if two of those branches, say the executive and judicial, worked in concert with one another they can absolutely work around, and even reinterpret, the Constitution. Elected representatives in the legislative branch would be virtually powerless to stop it. This is one of the most interesting (and important) byproducts of the Trump presidency. It has exposed serious flaws in the checks and balances that many of us thought existed as “law” when in fact it was only accepted practice and not actually enforceable.

For example, those who study the executive and legislative branches argue Congress has ceded far too much power to the presidency. Kevin Kosar, a conservative writer, tackled this issue in 2015 (and again since):

The Founding Fathers set up Congress as the most powerful of the three branches. Per the U.S. Constitution, Congress possesses “all legislative power.” This includes the most fundamental tools of governance and state-building, such as laying and collecting taxes, coining money and regulating its value and deciding what persons may join the nation as citizens. …

The Founders erected a remarkable system of government. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition, in Madison’s famous dictum, and each branch would defend its powers from encroachment. Unfortunately, Congress has not worked that way for at least a half-century. In the pursuit of other goals, Congress has weakened itself as an institution and representative government as a whole.

👑The unitary executive theory

The “unitary executive theory,” an idea advanced by conservative constitutional law experts, holds that the president of the United States possesses the power to control the entire executive branch regardless of legislative action. The doctrine is rooted in Article II of the Constitution, which vests "the executive power" of the United States in the president. Although that general principle is widely accepted, there is disagreement about the strength and scope of the doctrine.

It was originally rather innocuous, but extreme forms of the theory have developed and been exploited by every president since George W. Bush, and Trump took it to new depths. As Ronald Reagan’s White House counsel John Dean explained:

"In its most extreme form, unitary executive theory can mean that neither Congress nor the federal courts can tell the President what to do or how to do it, particularly regarding national security matters."

Despite what its proponents may argue, the unitary executive theory is not closely aligned with the original design for the executive office created under the Constitution.

Indeed, it threatens the delicate balance of powers by justifying power grabs by the president. Unfortunately, in Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Supreme Court in 2019 ruled that the president has absolute authority to remove the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), striking down a key provision of the law that created the agency in 2010. While narrow, the logic of this troubling decision could undermine the longtime practice of structuring executive branch agencies in ways that insulate certain federal officials from undue political control or pressure from the White House. This type of independence is essential to government integrity and the rule of law, and it was under constant assault by President Trump. This logic takes the court another step closer to a more absolutist vision of the unitary executive theory, which tolerates no checks on the president’s power within the executive branch. In its most extreme form (championed by the late Antonin Scalia and espoused by at least two of the sitting justices), the philosophy would not permit any statutory limits on the president’s ability to fire even those officials investigating his own conduct or that of his immediate subordinates.

Taken to the extreme it would eviscerate the very checks and balances the founding fathers felt were critical to our republic.

In an era when so many other constraints on the abuse of presidential power are already buckling, this is an alarming prospect. From Trump’s interference in independent counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, to the favorable treatment the Department of Justice has accorded to Trump allies like Michael Flynn and Roger Stone, to the firing of the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York — who was overseeing investigations of the president’s associates — under Trump we witnessed unprecedented politicization of law enforcement.

Watchdogs charged with performing independent oversight in the executive branch were also under attack during the Trump administration. The former director of the Office of Government Ethics — the executive branch’s ethics watchdog — resigned from his post after facing efforts by the Trump administration to limit his authority, as well as baseless accusations of misconduct. Trump removed several inspectors general, apparently in retaliation for their scrutiny of alleged misconduct by himself and other senior government officials, and to thwart oversight of his administration’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The president even tried to harness the regulatory authority of independent agencies to pursue political vendettas, as in one executive order seeking to have the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission reconsider whether Twitter (now X) and other online platforms that he deems biased against conservatives should be made liable for statements made by their users. These actions may be motivated by the president’s political and personal whims, but they also serve the long-term ideological aim of aggrandizing presidential power even in the most extreme cases. Bill Barr, who served as attorney general under Trump, has been involved in many of these instances and has made his legal career in government defending the unitary executive theory.

For now, the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence appears to leave significant room for Congress to check such abuses of power by insulating some parts of the executive from the president’s absolute control. Among other things, the decision takes pains to preserve two limited “exceptions” from the broad unitary executive theory it articulates.

The first, for so-called “expert” agencies led by a group of officeholders “balanced on partisan lines,” is plainly intended to cover the many long-standing, multimember commissions to which Congress has given significant power and autonomy, including the FCC, FTC and Federal Election Commission.

The second, for so-called “inferior officers” who need not be subject to Senate confirmation, covers the civil service, plus certain officials with high-profile but “limited” roles like prosecutors. Here’s an interesting article from the Cato Institute, a Libertarian (e.g., right wing) think tank, that examines this issue: "Reining in the Unreasonable Executive. The Supreme Court Should Limit the President’s Arbitrary Power as Regulator."

I hope you can see where all this is heading. The Council on Foreign Relations published a great piece, "The Unconstrained Presidency: Checks and Balances Eroded Long Before Trump," which points out that Trump wasn't the first to advance an aggressive interpretation. But to me, this is a critical reason why we must repudiate Trump or his example will inspire others to go further.

In November 2023, the Supreme Court heard a three-part case on the constitutionality of the Securities and Exchange Commission that will have broad implications for the unitary executive theory when the justices issue their ruling.

As one would imagine, the left and the right have very different points of view on the case.

On the right, George Will notes in a Washington Post column that the case will have “momentous implications for government power.” If the court rules in favor of Jarkesy, he wrote:

the constitutional right of access to courts will be vindicated, constitutionally dubious delegations of congressional power will be curtailed, and administrative state agencies will have to respect the separation of powers. Let us hope for what progressives fear: the end of government as they have transformed it. …

Many targets of SEC enforcement quickly settle cases that the SEC assigns not to a regular court with a neutral judge but to its in-house tribunals. This practice is analogous to prosecutors overcharging defendants to coerce them into plea bargains, vitiating their right to jury trials. …

By resisting such abuses, Jarkesy, like the Institute for Justice, is defending the nation’s constitutional structure against unaccountable agencies operating as a fourth branch of government. Jarkesy is asking the Supreme Court to demonstrate, for the benefit of everyone but administrative state bureaucrats, something that Alexander Hamilton said (in Federalist 78) would be required to defend the Constitution against depredations by the elected branches: an ‘uncommon portion of fortitude.’

On the left, Ian Millhiser wrote in Vox that court “could help make Trump’s authoritarian dreams reality.”

We are talking about a federal agency that has existed since the Roosevelt administration, and whose governing statutes haven’t changed in any relevant way for more than a dozen years. Nevertheless, an especially right-wing panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit purported to find three entirely different constitutional flaws that somehow no one else has ever noticed before. …

“None of the three rationales the Fifth Circuit offered for neutering the SEC are especially persuasive, but one of them is grounded in a pet project of the conservative Federalist Society known as the ‘unitary executive’ — a project for which the current Court’s GOP-appointed majority has shown a great deal of sympathy.

There is a risk, in other words, that at least some of the Fifth Circuit’s effort to light this decades-old agency on fire could succeed, with implications that stretch far beyond securities fraud. A sweeping decision affirming the Fifth Circuit could potentially enable former President Donald Trump to stack the federal civil service with MAGA loyalists, should he become president again,” Millhiser said. “If the Court comes for ALJs in the Jarkesy case, however, that will be far more than a symbolic step toward the unitary executive theory… a decision striking down these ALJs would destroy much of the government’s ability to adjudicate cases.

And then there is Isaac Saul in Tangle News:

The reason this argument is striking is its simplicity: A president is the chief executive, and they should have broad control over the executive branch. If a president can't do something as simple as fire an employee in the executive branch, it feels as if they are being deprived of a fundamental power granted to them by the Constitution. That, paired with the precedent set in the 2010 Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board ruling, makes me think Jarkesy might get some traction here.

Of course, as Ian Millhiser pointed out, the logical extreme of the theory of the unitary executive is that a president could get elected and then lay off the entire federal workforce if they wanted to. That doesn't seem like a safe or reasonable way for the government to function, which is why so many good arguments against the theory have been crafted over time. But I suspect the theory will find some friendly ears on this court.

The Roberts court had tended toward incrementalism, and I doubt it will take any of these three arguments to their logical extremes. Given the makeup of the court, I think a much more likely outcome is that Jarkesy scores a narrow but significant victory that limits agency and administrative power but causes the least amount of disruption to the federal government. How will the court reach that conclusion? I’ll say it again: I really don’t know.

I am personally torn on this subject because I do believe the federal government has overreached, particularly the executive and legislative branches, from a constitutional perspective, but I also know that appropriate checks and balances must exist to ensure that grave injustices aren't perpetrated on the unsuspecting public. I also know that resting too much power in the executive branch has far-reaching and highly disturbing implications for the country.

We will see what the Supreme Court decides. But there is no doubt that the Trump administration packed the federal courts (including SCOTUS) with conservative justices who will shape the future of our country for decades to come.

I continue to believe that we must unrig the system to bring common sense back to our politics so that we can allow our elected representatives to ensure that we rebalance and check the power of the three branches of government.

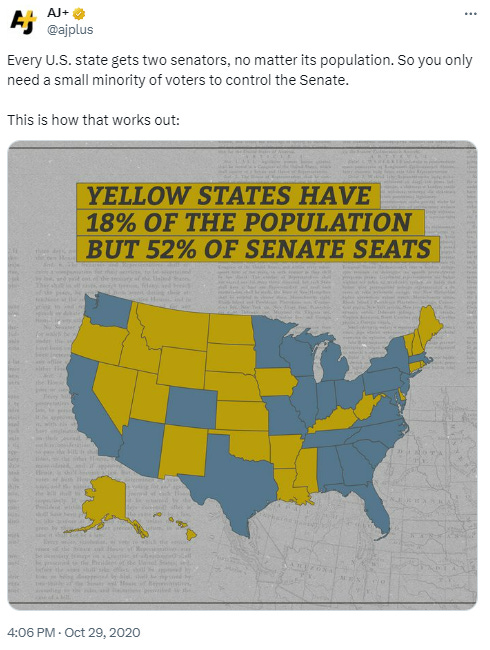

🏛️The Senate

During the Constitutional Convention, representatives of large and small states were divided over how to structure the legislative branch. Large states wanted a proportional system, granting them more seats and thus more power. Small states wanted equal representation, regardless of population. The resulting compromise gave us a bicameral structure: the House of Representatives is apportioned based on population (six states have one member; California has 52) and the Senate, with two members per state. (And, it should be noted, Americans living in D.C. and other territories do not have any voting representatives in Congress.)

The Senate has become more undemocratic in terms of its unequal representation of its citizens than it has ever been. The citizens of more populous states such as California, Florida, and Texas are radically underrepresented while states like Alaska, Vermont, and Wyoming are grossly overrepresented. Those same issues persist in the Electoral College as well.

According to The Atlantic, that “disproportionate influence of small states has come to shape the competition for national power in America.”

Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential elections, something no party had done since the formation of the modern party system in 1828. Yet Republicans have controlled the White House after three of those elections instead of one, twice winning the Electoral College while losing the popular vote.

The Senate imbalance has been even more striking. According to calculations by Lee Drutman, a senior fellow in the political-reform program at New America, a center-left think tank, Senate Republicans have represented a majority of the U.S. population for only two years since 1980, if you assign half of each state’s population to each of its senators. But largely because of its commanding hold on smaller states, the GOP has controlled the Senate majority for 22 of those 42 years.

Moreover, the Supreme Court confirmations of Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, as well as the midterm elections of 2018 (in which Republicans increased their Senate majority while losing control of the House), illustrate how senators representing a minority of the total population can now make momentous decisions that are often contrary to the views of the majority of the nation’s citizens.

In 1995, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.) recognized the looming imbalance and called for a change: “Sometime in the next century the United States is going to have to address the question of apportionment in the Senate.”

Perhaps that time has come. Today the voting power of a citizen in Wyoming, the least populous state, is about 67 times that of a citizen in the largest state of California, and the disparities among the states are only increasing. The situation is untenable.

Pundits, professors, and policy makers have advanced various solutions. Burt Neuborne of New York University has argued that the best way forward is to break up large states into smaller ones. Akhil Amar of Yale Law School has suggested a national referendum to reform the Senate. The retired congressman John Dingell asserted that the Senate should simply be abolished.

In his article entitled "Senate Democracy" Eric W. Orts proposes to make the Senate more democratic through the adoption of a Senate Reform Act that would reallocate the number of senators to each state by relative population.

Here is our situation in two graphics:

(Read more about these numbers in the National Review.)

As discussed earlier, the framers envisioned the Constitution evolving as our country evolves. Yet, we are stuck with a construct that is out of touch with the realities of America today.

Sadly, absent a second Civil War (obviously an unacceptable option), passing a constitutional amendment to address this imbalance is near impossible given the fact that it requires the approval of three-quarters of the states and two-thirds of the House and Senate.

Later I will identify organizations that are working to unrig the system. For them to be successful in implementing the important reforms needed, we must pass several constitutional amendments. But before we can take that step, we need to elect more common sense leaders capable of putting the country ahead of party to ensure that our government aligns with the governed!