Ch 1.12 | 🗳️Plurality voting

The majority of elections in the United States are won by the candidate who simply wins the most votes. At face value, that seems like a simple system. But such elections create the possibility, if not the likelihood, that the winner will capture less than a majority — a mere plurality — of votes. Let’s consider the implications of that kind of election and some alternatives.

The spoiler effect

On five occasions, a presidential candidate who did not win the most voters still managed to win the White House through the Electoral College. While I wouldn’t be surprised to see it happen once more in 2024, such an unfair outcome need never happen again. In William Poundstone's book "Gaming the Vote: Why Elections Aren't Fair (and What We Can Do About It)", we find that the solution is lurking right under our noses.

In all five cases, the vote was upset by a "spoiler"―a minor candidate who took enough votes away from the most popular candidate to tip the election to someone else. The spoiler effect is more than a glitch. It is a consequence of one of the most surprising intellectual discoveries of the twentieth century: the "impossibility theorem" of the Nobel laureate economist Kenneth Arrow. His theorem asserts that voting is fundamentally unfair―a finding that has not been lost on today's political consultants. Armed with polls, focus groups, and smear campaigns, political strategists are exploiting the mathematical faults of the simple majority vote.

So why is Plurality Voting enabling this "spoiler effect" and in doing so keeps the existing system rigged against us?

Leading political reformer Katherine Gehl gave a TEDx talk where she made the case that plurality voting is a major problem facing our nation. She believes that our current system’s ensures the duopoly — the Democratic and Republican parties — maintains the status quo, continues to eliminate competition, and provides a disincentive for politicians to work across the aisle towards progress and solutions instead of just reelection.

Gehl and and her writing partner Michael Porter present their analysis of the extreme political dysfunction that exists today and the resulting negative impact on U.S. competitiveness. In their report they said:

The politics industry is different from virtually all other industries in the economy because the participants, themselves, control the rules of competition.

Alternatives to plurality voting

Just because most of use one voting system doesn’t mean that’s the best way to do it. In fact, there are a number of alternatives worth exploring — each of which offers advantages over plurality voting.

FairVote is a leading advocate for ranked-choice voting, the most widely used alternative in the United States.

There are many ways of conducting an election. Voting for one and ranking candidates may be most familiar, but voting could mean any means of expressing opinion on candidates or issues. How those votes translate into a winning candidate can be even more varied.

FairVote has researched several of the most common voting methods, both as used in public elections and those that have been merely theorized for use in public elections. FairVote’s research demonstrates that ranked choice voting is the most empowering and effective voting method for use in United States elections.

The following chart compares the most widely discussed voting methods for electing a single winner (it does not address multi-winner election methods). There are countless criteria by which voting methods can be assessed, but the criteria at the top of the list are those we identify as the most important for U.S. public elections.

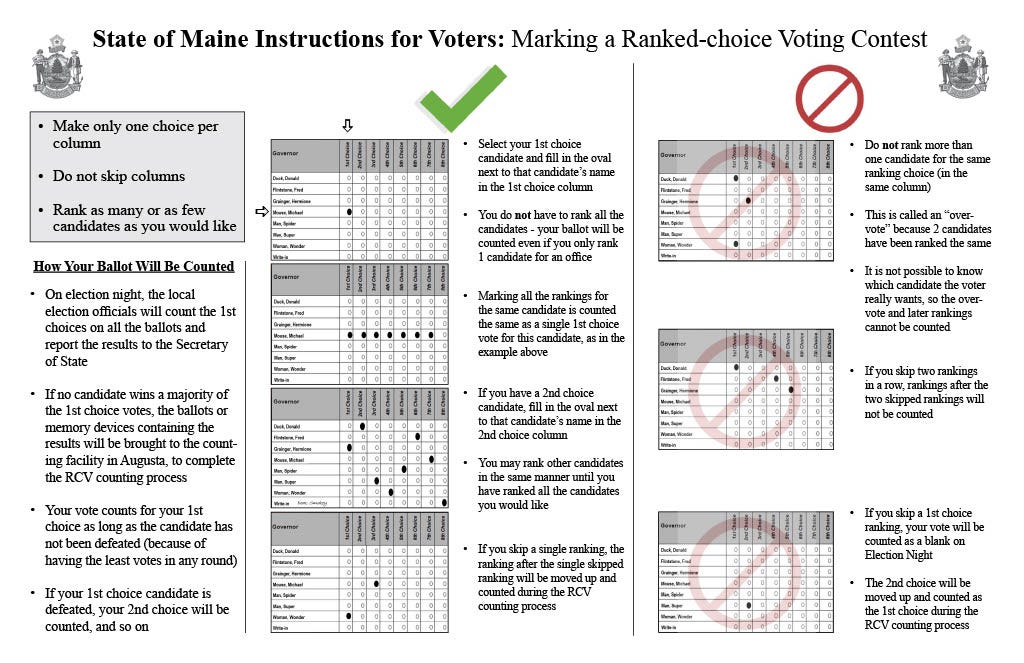

In a ranked-choice voting (also known as “instant runoff) election, voters are asked to rank the candidates on their ballot from most to least favorite. Sometimes voters are limited to a certain number candidates they may rank. Here’s a sample ballot from Maine, which uses RCV.

If a candidate gets a majority of the top votes, they win. If not, candidates with the fewest first-choice votes are sequentially eliminated and those next-preference choices transfer over in subsequent rounds. That continues until a candidate has more than half the remaining first-choice votes. Opponents claim the system is complicated, but it has proven to be popular.

Alaska uses a version of RCV championed by Gehl: "final-five voting" (except the state limits the final round to four candidates). Unlike a plurality system where third-party candidate usually serves as a spoiler, this structural reform is not a “trojan horse for partisan advantage” — its implementation doesn’t benefit one “side” more than the other. In discussing final-five voting, Gehl states:

Final-Five Voting is not designed to necessarily change who wins. It’s designed to change what the winners have the freedom to do and are incented to do—and on whose behalf they’re doing it.

Final-five voting will reward candidates and parties that run the best campaigns, appeal to the most voters in the general election (not just to partisan primary voters) and do the better job of governing once in office.

In addition to Maine and Alaska, RCV is used in New York City, San Francisco, Minneapolis and dozens of other cities and counties.

Poundstone favors another alternative to plurality voting known as range, or score voting. In this alternative, voters score each candidate. For example, they could rate each candidate on a scale from 0-9. The candidate with the most points wins. He writes:

The answer to the spoiler problem lies in a system called range voting, which would satisfy both right and left, and Gaming the Vote assesses the obstacles confronting any attempt to change the U.S. electoral system.

Unfortunately, range voting has not yet been used in any public election in the world and has only been used by very few private associations. As such, this is not a viable alternative.

Another alternative is approval voting, which allows voters to choose any number of candidates. The candidate chose on the most ballots wins. Approval voting is most often discussed in the context of single-winner elections, but variations using an approval-style ballot can also be applied to multi-winner (often at-large) elections. Note that the tallying process is often different there.

While ranked-choice voting has been around longer and is more well known, the Center for Election Science and other proponents of approval voting say their preferred method is simpler for voters, easier to tabulate and less expensive to manage. CES claims:

Computer simulation studies show that approval voting is superior to RCV as measured by “Bayesian regret“, an objective measure of average voter satisfaction. The following graph, taken from page 239 of William Poundstone’s book Gaming the Vote, displays Bayesian regret values for several different voting methods, as a function of the amount of tactical voting.

Of course, there are opponents to approval voting. FairVote, for example, cited two areas of concern:

Viability and the issue of majority rule : If voters truly are free with their approvals in an approval voting election, it’s quite possible two or more candidates could earn more than half the vote. Indeed, it’s possible that a candidate whom well over half of voters see as a top choice could lose to someone who nobody sees as their top choice. Approval voting advocates defend such outcomes as fair, but it remains to be seen what voters would say.

Workability in the real world: In approval voting elections, you can’t indicate support for more than one candidate without support for a lesser choice potentially causing the defeat of your first choice. This transparent dilemma for voters trying to cast a smart vote has immediate consequences. Because most voters as a result of this problem will refrain from approving of more than one candidate, the system in practice ends up looking far more like a plurality voting election system than a majority system.

Approval voting is used in St. Louis and Fargo, N.D.

Lack of competition is corrupting our elections

Beyond how the parties have corrupted the elections process and disenfranchised the majority of voters in America, they have also twisted the legislative system itself to ensure they control the process. One example is the duopoly-created fundraising rules allow a single donor to contribute $855,000 annually to a national political party but only $5,600 per two-year election cycle to an independent candidate committee.

Another is something called the "Hastert Rule," which we've all seen in practice but might not know it's history or implications.

As Gehl and Porter state:

"The Hastert Rule is a particularly egregious example of today’s partisan legislative machinery in action. Now standard practice—of Speakers of both parties—although in fact written down nowhere, the Hastert Rule dictates that the Speaker will not allow a floor vote on a bill unless a majority of the majority party—the Speaker’s party—supports the bill, even if a majority of the full House would vote to pass it. Unless Speakers ignore this practice—a rare occurrence—bipartisan bills that appeal to the minority party (in this example, the Democrats) and some of the majority party (the Republicans) are killed by never being introduced. Legislation supported by a majority of Americans and by a majority of the House has no chance of passing—in fact, is not even allowed to be debated—because there will never be a vote. The bill won’t reach the floor. No deliberation, no amendments, no votes. No transparency. No accountability. Effectively, this made-up rule, not found in the Constitution, not codified in law or even written in the House rules book, cements hyper-partisan control over the legislature.”

It's time to break the stranglehold that the Duopoly has on our country and re-introduce fair competition into the political system! If you're interested in learning more... read on!

Every industry has welcomed innovation and improvements as a result of competition… except one. The absence of competition in politics has led to a limited range of choices for voters, often perpetuating the status quo and stifling innovative approaches to improving our state.

I've come to conclude that it's not who we elect, or which party or policy we support, it’s all about fixing a system that isn't delivering the outcomes that are in the best interests of America. There are a few structural reforms that are gaining traction that have the potential to have a profound effect on our democratic republic. To name a few that are top of mind that I will cover in this paper, I believe we need to open our primary system, eliminate the "spoiler effect" inherent in our political duopoly to enable increased competition and expanding the voice of the electorate in our elections, reform campaign finance laws and pass a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United and remove political gerrymandering to name a few.

It's time for a new, fair, and competitive system that serves the interests of the people, not just a select few. As I outline in “Unrigging the system," I firmly believe that the best way to make a difference, is for each of us to come together and help support and facilitate some incredible organizations that are dedicated to instilling fairness into our election process and thereby ensure proportionate representation is returned to Washington DC.

Lack of Competition is Corrupting our Elections.

Beyond how the parties have corrupted the elections process and disenfranchised the majority of voters in America, they have also twisted the legislative system itself to ensure they control the process. One example is the duopoly-created fundraising rules allow a single donor to contribute $855,000 annually to a national political party but only $5,600 per election cycle — two years — to an independent candidate committee.

Another is something called the "Hastert Rule." We've all seen it in practice, but some may be unaware of it’s history and implications.

As Katherine Gehl and Michael Porter state:

The Hastert Rule is a particularly egregious example of today’s partisan legislative machinery in action. Now standard practice—of Speakers of both parties—although in fact written down nowhere, the Hastert Rule dictates that the Speaker will not allow a floor vote on a bill unless a majority of the majority party—the Speaker’s party—supports the bill, even if a majority of the full House would vote to pass it. Unless Speakers ignore this practice—a rare occurrence—bipartisan bills that appeal to the minority party (in this example, the Democrats) and some of the majority party (the Republicans) are killed by never being introduced. Legislation supported by a majority of Americans and by a majority of the House has no chance of passing—in fact, is not even allowed to be debated—because there will never be a vote. The bill won’t reach the floor. No deliberation, no amendments, no votes. No transparency. No accountability. Effectively, this made-up rule, not found in the Constitution, not codified in law or even written in the House rules book, cements hyper-partisan control over the legislature.

It's time to break the stranglehold that the duopoly has on our country and re-introduce fair competition into the political system!

Every industry has welcomed innovation and improvements as a result of competition … except one. The absence of competition in politics has led to a limited range of choices for voters, often perpetuating the status quo and stifling innovative approaches to improving our state.

I've come to conclude that it's not who we elect, or which party or policy we support, it’s all about fixing a system that isn't delivering the outcomes that are in the best interests of America. There are a few structural reforms gaining traction, which have the potential to have a profound effect on our democratic republic. To name a few:

Eliminating the "spoiler effect" inherent in our political duopoly to enable increased competition and to expand the voice of the electorate in our elections.

Reforming campaign finance laws and pass a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.

It's time for a new, fair and competitive system that serves the interests of the people, not just a select few. The best way to ensure proportionate representation is returned to Washington, D.C. is for each of us to support and facilitate some incredible organizations that are dedicated to instilling fairness into our election process.